After running your gel and transferring your proteins to your membrane, there is one thing left for you to do to ensure the accurate analysis of your protein. You need to block all unoccupied sites on your membrane to prevent the non-specific binding of antibodies and other detection agents to your membrane during subsequent steps. If you take this step lightly, you'll risk compromising the reliability your results.

After running your gel and transferring your proteins to your membrane, there is one thing left for you to do to ensure the accurate analysis of your protein. You need to block all unoccupied sites on your membrane to prevent the non-specific binding of antibodies and other detection agents to your membrane during subsequent steps. If you take this step lightly, you'll risk compromising the reliability your results.

While the Western blot assay provides a lot of valuable information about your protein of interest, its accuracy and reliability may depend largely on the signal to noise ratio of the results. Western blot may have problems with specificity so blocking is considered to be of utmost importance.

Why is Blocking Important?

Blocking is one of the most critical steps when performing Western blot and ELISA experiments. By using the appropriate blocking buffer, the signal-to-noise ratio can be improved while background staining can be significantly reduced. You'll know you are doing something wrong if you end up with too much background noise. Ideally, what you want to see is a beautiful band representing your protein of interest with minimal background so you can accurately assess and analyze your protein of interest.

How Do You Choose Which Blocking Buffer to Use?

There are three things to consider when choosing a blocking buffer – your protein of interest, your antibody and the detection system that you are using. Basically, there are seven common blocking buffers used in the laboratory, which includes:

- Skim milk powder – While skim milk is definitely the cheapest and most readily available blocking buffer available, it contains a number of proteins that may interfere with your results, especially if you are trying to detect a phosphorylated protein or are working with avidin-biotin systems.

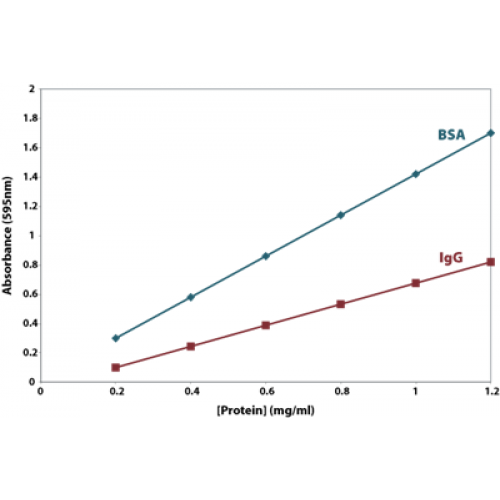

- Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) – BSA is one of the favorite blocking buffers used in the lab but it can also be quite expensive. Unlike skim milk, however, it can be used when detecting phosphoproteins. BSA should not be used if you are working with anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies and lectin probes.

- Normal serum – While fetal calf serum, rabbit serum, horse serum and goat serum can be used as blocking agents, they are not widely used in the lab due to their high cost. Additionally, whole serum contains immunoglobulins that may cross-react with mammalian antibodies.

- Fish gelatin – Fish gelatin is unique since it remains liquid even at extremely low temperatures and doesn't cross-react with mammalian antibodies. However, it is not recommended for blocking biotin detection systems since it contains endogenous biotin.

- Purified casein – Basically, purified casein can be used in applications where you would use skim milk powder but it also has the same limitations.

- Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) – PVP is one of the newest blocking buffers available today. It is generally used in combination with other blocking agents and is ideally used in detecting small proteins.

- Commercial buffers – Commercial buffers may be more expensive but they do not contain any traces of phosphoproteins, albumin, biotin or immunoglobulins. They also allow you to proceed more rapidly with your experiment.

Theoretically, you can use any blocking buffer that does not have an affinity to bind with your target or probe components but in actual practice, some perform better than others. For best results, choose a blocking solution that provides the best signal-to-noise ratio.

Still Having Problems with Non-Specific Binding?

Here are some things you may want to consider if you continue to encounter this problem.

- Increase the incubation period and/or temperature to ensure complete blocking.

- Increase the concentration of your blocking buffer.

- Add 0.1% Tween in your buffer to prevent cross-reactivity between your blocking agent and your antibodies.

- Use an entirely different blocking buffer.

When addressing non-specific binding, make sure you change one factor at a time to accurately identify the problem. However, please note that not all non-specific bands are a mistake. The presence of multiple bands on your blot may not always be caused by technical artifacts. They may simply be variants of your protein of interest, especially if the same bands appear consistently on your blots.